The $237 million contract awarded by Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) for a seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plant represents a big step for the client, and for Besix Concessions & Assets, which won the work in partnership with Acciona Agua.

For DEWA, the project is a decisive step on the road to building up its capacity in reverse osmosis desalination, as part of an ambitious strategy to reduce reliance on thermal desalination during the coming decades, to improve efficiency, cut costs, and reduce carbon emissions.

Meanwhile for Besix Concessions & Assets — one of three business units within Besix Group, which also includes Besix Contracting, and property developer Besix Real Estate — the contract win is a vindication of its strategy to compete for design and build work in desalination, because this was the first tender it entered. The size of the project also makes it significant for Besix Group, whose entire turnover is about $3 billion a year globally (about 40 per cent of which comes from the Middle East).

Entrepreneurial energy

- Fully open book integrated joint venture of Besix and Acciona

- Joint venture will hand operations to DEWA after two years

- First bid by Besix for the engineering, procurement and process design elements of a desalination project

A joint venture of Belhasa Six Construct (Besix), and Acciona Agua won an AED 871 million ($237 million) desalination project from Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) in March 2018. The contract covers a 40 million imperial gallons (MIGD) a day (182,000 m3/d) seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant and associated facilities, including intake, outfall, pre-treatment and a two-pass reverse osmosis system. The date for commissioning is May 2020, and the joint venture will operate the plant for a two-year warranty period.

The contract win is significant for Besix Concessions & Assets, because it’s the first time the company has bid for the engineering, procurement and process design elements of a desalination project. Besix has a long history of operating in the Middle East, particularly as a marine contractor, and has a fleet of hundreds of barges, dredgers and other vessels, all designed, built and owned in-house. It has constructed very many of the seawater intake and outfall structures, plus the related pumping stations and civil environments, for seawater desalination and power plants dotted around the Gulf.

“We may be one of the top five water contractors in the world, but what we have been lacking is the process side, we basically stopped at the civil and marine work, but we could not do the engineering and procurement and process design,” says Rolf Keil, project development manager, Besix Concessions & Assets. “A couple of years ago the company had a vision to develop and grow for the future, especially taking into view the upcoming public-private partnership (PPP) model that is being employed across the region. That vision is what Concessions & Assets has developed into a reality, and that is what I was hired to lead.”

Besix Group has strong roots in the Middle East, in some cases working with sponsor families in relationships reaching into the second and even third generations. It has built some of the most ambitious projects in the region, too, including the Burj Khalifa skyscraper in Dubai, Dubai Water Canal, the Emirates Palace hotel, Abu Dhabi; and back in the 1960s, Sultan Qaboos Port, in Muscat, Oman.

At about a quarter of a million dollars, the investment is sizeable for a group whose entire revenue is around $3 billion. And the nature of the model employed by Besix and Acciona — an integrated, open book joint venture — is a significant step. “Because each side opens their books to the other. We know exactly how much one pays for a kilo of concrete, and the other knows exactly for how much to buy the pumps, and we can challenge one another about what is the best optimised process. It’s not like two entities working separately and then each pops up with a price. We are working together in the same office, same teams, fully open book. It’s a fantastic experience, and one of the first times that this has been done here at Besix,” explains Keil, adding that the joint venture has instilled an entrepreneurial energy in the project that is helping to drive innovation and efficiencies. In particular, it cuts out the contingencies that are often put into a project to allow for unknowns or pitfalls that may occur due to lack of detailed knowledge about a partner’s approach. “If we can sit together and challenge what would be the best idea how to do it, then I have a very close and sharp knowledge of what I really need to do, and I can be much more competitive and more accurate to reality,” he says.

Site and design

- Design-led engineering reimagines buildings over one storey, and not two

- Located in Jebel Ali industrial zone

- Project is more accurately described as greenfield than brownfield

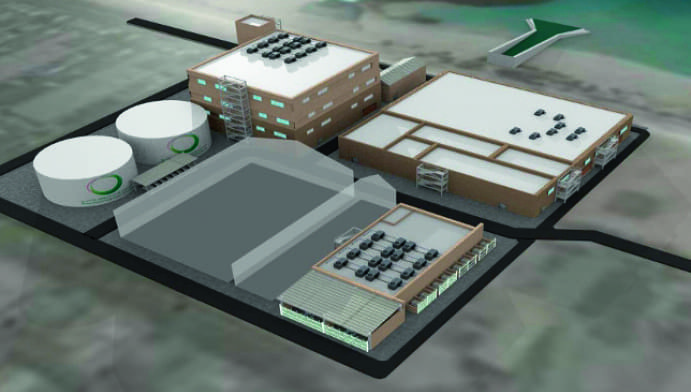

The project has been billed as a brownfield scheme because it’s sited in an industrial zone; in fact, it would more accurately be described as greenfield, because the allotted space is vacant and has no existing assets that require demolition, modification, or integration. The site is U-shaped, and is surrounded by lots filled by industrial operators and their associated infrastructure, including power and gas installations. “The design is a little bit complicated for the intake and pumping station because we need always to find the gaps in between the neighbours,” explains Keil.

The main design challenge was to fit everything onto the compact site. In the consultant engineer’s original designs, the process buildings were foreseen as two-storey to accommodate all the process equipment. “That makes the whole structure more expensive to build. Through our experience as a contractor and designer, we could optimise certain buildings and structures, and together with Acciona, we saw how to fit the process into it, and we were able to put everything onto the ground floor, and could be very competitive,” says Keil.

As part of the design process, Besix drew on its back catalogue in building power and water plant intake infrastructure systems, including how other customers wanted to solve similar puzzles. “This made us very competitive, and enabled us to stay fully compliant with the specifications and requirements of both the client, DEWA, and its consultant ILF,” he adds. Further, keeping all the buildings to a single storey has a positive effect on the future cost to DEWA of owning and operating the plant. “Just imagine, if you need to pump your water onto the first floor, the cost of extra pumps, electricity. We are saving on that cost every day for 30 years. The approach that we took was, ‘what if I had to operate it for the next 25 years.’ If you think like that, you will challenge yourself in a much smarter way,” Keil says.

Technology and efficiency

- Plant performance “significantly improves” on industry average energy consumption

- Large size Dissolved Air Flotation and Dual Media Gravity Filtration systems

- Proprietary energy recovery technology that utilises brine

The project team brought innovation to its technology and process design: The intake infrastructure and pumping station are to be built new, and the team had to find routes and channels under roads and around neighbouring structures. The project will use a pipe intake reaching 1.2 kilometres into the sea, and an outfall pipe of two kilometres — in line with the Environmental Impact Assessment, and relevant environmental regulations. “We looked at the currents, and at the nearby coral reefs. We decided to go a bit further, to protect those,” says Keil.

The pumping station is about 16 metres in depth, and water is pumped into a Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) unit of 26 metres by 110 metres, which typically has 99 per cent recovery. From the DAF, the water goes to a dual media gravity filtration (DMGF) system of 50 metres by 95 metres, partly above and partly below ground, with a hydraulic design making it more economical. Any sludge from the DAF or DMGF is sent to a thickening treatment system, and then into a centrifuge and trucked for recycling or fertilisation. “This is something that DEWA will take the benefits from, and that we included in our design thinking as developer,” adds Keil.

After the DMGF, the water goes through a typical two-pass RO — seawater RO followed by brackish water RO — and then for remineralisation. “Remineralisation is a difficult process that must be done correctly, that includes limestone filters, and introduction of minerals to make it good quality drinking water,” says Keil. There is a proprietary technology for energy recovery from brine, and a brine treatment process, before the final waste brine is discharged back into the ocean.

“The design requirements from DEWA and ILF were super challenging, but from our perspective it is a pleasure to work in such an environment, because if they set the technical requirements very high, and you come with real value engineering, it makes a difference. It’s not necessarily the quickest and cheapest, but what you can achieve is outstanding. If we had to sell the water as owner of an Independent Water Plant, it would be a very competitive rate,” Keil says.

The new plant “significantly improves” on industry average energy consumption, he adds.

Treatment train

“The main process structures, the brine concentration, Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF), the dual media filtration, the reverse osmosis (RO) building, the calcite filter, the chemical building, and the flush treatment, as well as the RO clean-in-place, the electro-chlorination drainage — in the original plans, all these were to be on top of each other in a two-storey building that would take up about 60 percent of the plot, and the rest, the left and right legs, would be for the potable water storage tank, the outfall, and the electrical building. We swapped the left and the right leg. We put the tanks and electrical buildings on the opposite side, and having done so we discovered that we had the electrical building much closer to where we have the high pressure pump, and then we reconfigured our process: If you have two rectangular shapes and turn them around by 90 degrees, you can try to fit them into a particular framework, and this is what we have done. We were able to fit everything into the perimeter quite comfortably.” Rolf Keil, project development manager, Besix Concessions & Assets